A nice journalistic piece by Alexa Clay in Aeon on what it takes to be a viable intentional community.

A fascinating article from Christianity Today looks at how some American Christians are turning to cohousing to address was columnist David Brooks calls “a crisis of solidarity, a crisis of segmentation, spiritual degradation, and intimacy.” Check it out.

http://www.christianitytoday.com/women/2016/november/cohousing-new-american-family.html

The Atlantic ran a nice story about a income-sharing commune in Washington DC which resembles the Lotus House, at least superficially.

The 5-minute video story is here: “The Pros and Cons of Living in an Income Sharing Community.”

Unlike the Compersia Communune, we do not practice full income sharing (or “common purse” as it’s usually called in Christian community circles). Many communities, such as our sister community Reba Place Fellowship, do. Like Compersia, however, we seek to witness a better way of life grounded in hospitality, friendship, and cooperation.

The biggest difference between a commune like this and a Christian community like ours is the commitment to the gospel. The woman in the video says that the people in the commune are bound by a “common love” – they love the idea of radical egalitarian community. A shared vision is an important part of any kind of community life, but there is a great danger in loving the idea of community, as Dietrich Bonhoeffer observed many years ago. True community, he says, can only come from love for one another. The economic and institutional structure of our common life is merely a means of loving and caring for one another more effectively in our daily lives. We believe that we love each other best when we rest secure in the knowledge of God’s love for us. As beloved children, always accepted, always forgiven, we are free to love each other in the same sort of way. There’s a song that we sing together when we have important meetings or retreats which sums this up:

A common love for each other

A common gift to the Savior

A common bond holding us to the Lord

A common strength when we are weary

A common hope for tomorrow

A common joy in the truth of God’s word

The DC commune seems to offer a deeper life to its members, and insofar as it continues to do so it shares in the love of Christ, the author of all life. But any endeavor built on a economic theory, a political ideology, or a theological concept is bound to fail – love alone can save us.

Recently, our friends Jonathan and Leah Wilson-Hartgrove had the opportunity to visit Western Italy, the place where European monasticism had its beginnings. You can read an account of their journey, along with reflections on the relationship between “old” monasticism and “new” monasticism at RedLetterChristians.org. Check it out!

I recently had the pleasure of contributing to a new volume on intentional community edited by our friend Charles Moore of the Brunderhof and published by Plough Publishing. Called to Community: The Life Jesus Wants for His People is broken into 52 chapters featuring classic meditations by the likes of Benedict of Nursia, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Dorothy Day, Jean Vanier, John Perkins, and many others, including our friends David Janzen (Reba Place, Chicago), Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove (Rutba House, Durham), Elizabeth Dede (Koinonia, Americus), Charles Moore (Bruderhof, Esopus)and Jodi Garbison (Cherith Brook, Kansas City). My own chapter, entitled “The Way,” traces the development of Christian communities from the earliest Christians to the present. I hope you’ll pick up a copy and share it with friends.

I recently had the pleasure of contributing to a new volume on intentional community edited by our friend Charles Moore of the Brunderhof and published by Plough Publishing. Called to Community: The Life Jesus Wants for His People is broken into 52 chapters featuring classic meditations by the likes of Benedict of Nursia, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Dorothy Day, Jean Vanier, John Perkins, and many others, including our friends David Janzen (Reba Place, Chicago), Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove (Rutba House, Durham), Elizabeth Dede (Koinonia, Americus), Charles Moore (Bruderhof, Esopus)and Jodi Garbison (Cherith Brook, Kansas City). My own chapter, entitled “The Way,” traces the development of Christian communities from the earliest Christians to the present. I hope you’ll pick up a copy and share it with friends.

Here’s what the publishers say about the book:

Why, in an age of connectivity, are our lives more isolated and fragmented than ever? And what can be done about it? The answer lies in the hands of God’s people. Increasingly, today’s Christians want to be the church, to follow Christ together in daily life. From every corner of society, they are daring to step away from the status quo and respond to Christ’s call to share their lives more fully with one another and with others. As they take the plunge, they are discovering the rich, meaningful life that Jesus has in mind for all people, and pointing the church back to its original calling: to be a gathered, united community that demonstrates the transforming love of God.

Of course, such a life together with others isn’t easy. The selections in this volume are, by and large, written by practitioners – people who have pioneered life in intentional community and have discovered in the nitty-gritty of daily life what it takes to establish, nurture, and sustain a Christian community over the long haul.

Whether you have just begun thinking about communal living, are already embarking on a shared life with others, or have been part of a community for many years, the pieces in this collection will encourage, challenge, and strengthen you. The book’s fifty-two chapters can be read one a week to ignite meaningful group discussion.

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood began airing in the 1960s and continued in syndication until 2006 (his legacy continues with PBS’s animated series Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood). The creator and host of the show, Fred Rogers, is well known. Less well known are his radical political positions. A recent book by Michael Long, Peaceful Neighbor: Discovering the Countercultural Mister Rogers (Westminster John Knox, 2015) explores some of these themes.

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood began airing in the 1960s and continued in syndication until 2006 (his legacy continues with PBS’s animated series Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood). The creator and host of the show, Fred Rogers, is well known. Less well known are his radical political positions. A recent book by Michael Long, Peaceful Neighbor: Discovering the Countercultural Mister Rogers (Westminster John Knox, 2015) explores some of these themes.

First, Rogers was a firm pacifist. His show began in 1968, at the height of the Vietnam War, and he shared his anti-war

beliefs in the very first week. In the 1980s he vehemently opposed the nuclear arms race; a war breaks out in Season 14 (1983) in the Neighborhood of Make Believe between King Friday XIII and the village of Southwood. Though the conflict was resolved, these episodes were so dark that PBS pulled them from the rotation of re-runs in later years.

Second, Rogers was a determined, if subtle, integrationist. Soon after King’s assassination in 1968, Rogers introduced Officer Clemmons, a black police officer brought in to keep order and stability in the Neighborhood. In one scene, Rogers and Clemmons are shown sitting side by side and soaking their feet together in a swimming pool. Rogers then grabs a towel and dries Clemmons feet in an unmistakable imitation of Jesus’ footwashing (Watch the scene, wi th commentary by Clemmons here.)

th commentary by Clemmons here.)

Rogers’ radical politics grew directly out of his Christian faith. He was an ordained Presbyterian minister. On lunch hour between takes, he would sneak out and study theology at nearby Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. Rogers’ commitment to the nonviolent, reconciling way of Jesus was uncompromising, and led him to confront the Powers (i.e., Congress, the Media, and Pop Culture) at various times; yet throughout his public and private life he maintained a disarming, child-like love for the world. Saint Fred, anyone?

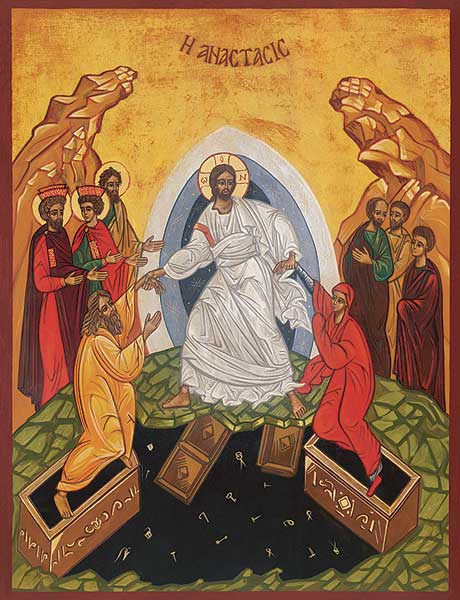

Christ is risen from the dead,

trampling down death by death,

and upon those in the tombs bestowing life.

~Orthodox Paschal Troparion

Happy Easter from the Lotus House!

From the Orthodox Liturgy of Holy Saturday

Today a tomb holds Him who holds the creation in the hollow of His hand; a stone covers Him who covered the heavens with glory. Life sleeps and hell trembles, and Adam is set free from his bonds. Glory to Thy dispensation, whereby Thou hast accomplished all things, granting us an eternal Sabbath, Thy most holy Resurrection from the dead.

Today a tomb holds Him who holds the creation in the hollow of His hand; a stone covers Him who covered the heavens with glory. Life sleeps and hell trembles, and Adam is set free from his bonds. Glory to Thy dispensation, whereby Thou hast accomplished all things, granting us an eternal Sabbath, Thy most holy Resurrection from the dead.

What is this sight that we behold? What is this present rest? The King of the ages, having through his passion fulfilled the plan of salvation, keeps Sabbath in the tomb, granting us a new Sabbath. Unto him let us cry aloud: Arise, O Lord, judge thou the earth, for measureless is thy great mercy and thou dost reign for ever.

Come, let us see our Life lying in the tomb, that he may give life to those that in their tombs lie dead. Come, let us look today on the Son of Judah as he sleeps, and with the prophet let us cry aloud to him: Thou hast slept as a lion; who shall awaken thee, O King? But of thine own free will do thou rise up, who willingly dost give thyself for us. O Lord, glory to thee.

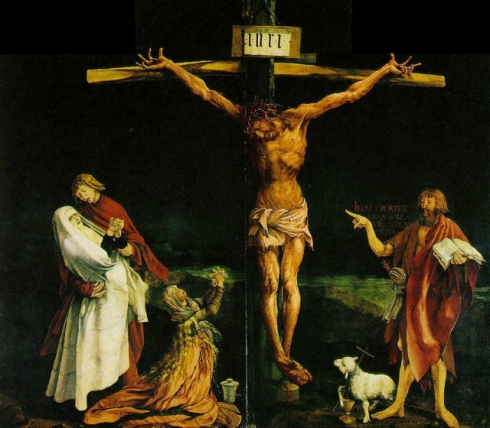

The Christian tradition has long held that the most persisting and infecting temptations we humans face is that of arrogating divinity into our humble humanity—remember the serpent’s words in the garden: “eat and you shall be like God.” The sufferings inflected upon the weak and the innocent throughout humanity’s history is nothing other than this perennial sin enacted: reaching beyond the pure gratuity of my own life to assert violently my will upon reality through murder. Theologian Rowan Williams fittingly calls this the “apocalyptic delusion”—the belief that we can assume the divine role of acting permanently in history by stamping out the life of another. Though we do not have the power to create out of nothing as God does, we assert the power to destroy and so claim dominion over reality. This is what we are remembering today, the time when we humans tried to appropriate a power we were not given—the power over life and death—and murdered the innocent Son of God. This is a day for introspection and repentance, for taking inventory of our own lives and asking if we are graciously receiving the life we’ve been given, or selfishly hoarding that which is not ours. We are always tempted to forget that we are creatures.

This day is more than that though. It’s not only a day when we remember our culpability for the sins of humanity; it’s a day when we remember that we fail at our sins. We try to act with apocalyptic finality, but it is a delusion, the infinite God who gives life sinks into death today, not as one who falls prey to its harsh finality, but as one who undoes death itself. The finite death we deal cannot contain the infinite God.

What we see in Good Friday is that God takes on not only human flesh, but human victimhood. All of the myriad voices that have been silenced throughout our blood-soaked history are not far from God, but are held by him as he embraces their victimhood in the solidarity of death. These voices that seem for all the world to be as still as dirt are given new life by God’s utter identification with them. Good Friday demonstrates that God remembers as one who suffers as a victim in history, not as a cosmic umpire inactively observing history unfold from a considerable distance. God is so close to the victims of history that his memory enfolds their memory. In Christ, God identifies himself as pure victim without a shred of guilt or violence in him, and receives into himself the extremity of humanity’s expulsive violence. Thus, God’s memory is not other than the victim’s memory, and his remembering is a literal re-membering, a making whole of what was broken, a giving again of what was taken; God redeems the past by taking it into himself and raising it in his resurrection.

Christ’s defeat of death through resurrection cleanses us of the presumption that the death we deal is final, that the suffering of history cannot be undone, that the only ultimate act in history is that act preformed by the executioner. Instead, he shows us that divinity is not the power or prerogative to judge and destroy, but is a wellspring of infinite creative love, and this is a divinity we are invited to arrogate to ourselves. Humanity acts with apocalyptic finality only when humanity imitates God in love. Love cannot be undone even by death, but death can, and indeed is, undone by love. The Christian answer to the problem of suffering in history is nothing other than the mystery of the cross and resurrection, of God’s revelation of himself as infinite and infinitely merciful, infinitely loving, and infinitely life.

O Thou Sun of Righteousness, eclipsed on the Cross, overcast with sorrows, and crowned with the shadow of death, remove the veil of Thy flesh that I may see Thy glory. Those cheeks are shades, those limbs and members clouds, that hide the glory of Thy mind. Thy knowledge and Thy love from us. But were they removed those inward excellencies would remain invisible. As therefore we see Thy flesh with our fleshly eyes, and handle Thy wounds with our bodily senses, let us see Thy understanding with our understandings, and read Thy love with our own. Let our souls have communion with Thy soul, and let the eye of our mind enter into Thine. Who art Thou who bleeding here causest the ground to tremble and the rocks to rend, and the graves to open? Hath Thy death influence so high as the highest Heavens? That the Sun also mourneth and is clothed in sables? Is Thy spirit present in the temple, that the veil rendeth in twain at Thy passion? O let me leave Kings’ Courts to come unto Thee, I choose rather in a Cave to serve Thee, than on a throne to despise Thee. O my Dying Gracious Lord, I perceive the virtue of Thy passion everywhere: Let it, I beseech Thee, enter into my Soul, and rent my rocky, stony heart, and tear the veil of my flesh, that I may see into the Holy of Holies! O darken the Sun of pride and vain-glory. Yea, let the sun itself be dark in comparison of Thy Love! And open the grave of my flesh, that my soul may arise to praise Thee. Grant this for Thy mercy’s sake. Amen!

From the writings of Thomas Traherne (c. 1637-1674)